Why are occupations at the UvA so popular?

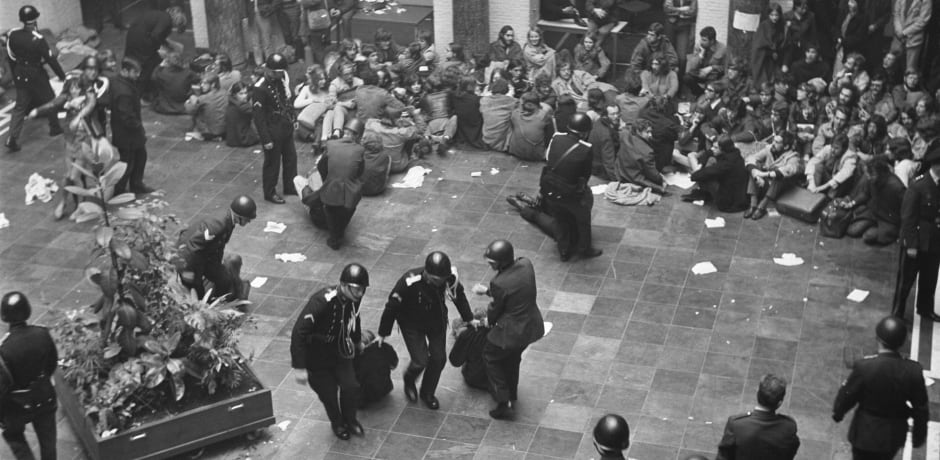

The black-and-white images from 1969 of policemen dragging resisting students out of the Maagdenhuis are very reminiscent of the pictures of ME officers dragging protesters from the Binnengasthuisterrein last May. What is the cause of so many rebellious UvA students? “Protest ideas still arise in lectures, in student residences or at get-togethers.”

A dozen students rush across a field on the Roeterseiland campus (REC). It is ten o”clock on Monday morning, May 6, and the sun is shining on their Palestinian scarves. The pro-Palestine students set up small tents and sit in a circle. “Something historic is going to happen today,” feels history student and protester Carlos van Eck (24), one of the students present.

However, nothing points to the battlefield that will take place fifteen hours later. Students will be beaten with truncheons, bricks will be thrown by protesters and the ME will subsequently demolish the erected barricades with brute force. The quiet meadow will become the battleground of a brutal confrontation between police and hundreds of protesters. The escalation is yet another in history. Where do these activist UvA”ers come from anyway?

Text continues below photo

1969

Location: Maagdenhuis

Goal: Greater student participation

Duration: Five days

Number of students: 400

Number of arrests: Unknown

Damage: 150,000 guilders

2015

Location: Bungehuis and Maagdenhuis

Goal: Democratization of university

Duration: six weeks

Number of students: 500

Number of arrests: 51

Damage: 500,000 euro

2024

Location: Roeterseiland and Binnengasthuisterrein

Goal: Break ties with Israel

Duration: Three days

Number of students: 600

Number of arrests: 161

Damage: 1,500,000 euro

Squatters

The occupation of UvA buildings by students is by no means new, says expert on UvA history Peter Jan Knegtmans. Knegtmans points to the many previous confrontations between police and students, such as during the multi-day occupations of the Maagdenhuis in 1969 and 2015 or the blockade of the P.C. Hoofthuis in 2018. “Amsterdam is simply a much bigger city than other university cities.” In proportion, the city has fewer students than a city like Groningen or Nijmegen. There, students form a large, homogeneous group, where in Amsterdam students more easily interact with other groups who also live there. UvA students are therefore more politically and socially engaged, according to Knegtmans.

Tim Verlaan, associate professor of urban history, also recognizes the involved and activist culture among young people in the capital. “For example, you see whenever there is housing shortage, past and present, that students radicalize. In the 1970s, that housing shortage created a squatter culture. Students started demanding their housing rights. They put up a bed, table and chair in squatting actions and with that, an empty house was taken possession of.”

During the 2015 Maagdenhuis occupation, squatters were also suspected by the UvA of taking the initiative to occupy the building. Verlaan: “Some of the most active students during last year”s Palestine demonstrations also had a squatter background. They therefore know better how to occupy a building.”

Student flat

Activist Van Eck explains that the protest movements underpinning the pro-Palestine protests in May this year also originated mainly in student flats. “Students at Amsterdam University College (AUC) – where the first blockades took place as early as early 2024 – all live together in flats on campus. Those students at one point wondered why nothing was happening at their university. So in January, AUC students started blocking their campus because they felt the university should review ties with Israeli universities. The same students were behind the larger-scale occupations on REC and the Binnengasthuisterrein, which followed in May.”

Students also started their actions in locally organized groups during the five-day occupation in 1969. Students had long been calling for greater student participation within the university. As in 2024, the protesters simply got to know each other in student life. In 2019, for instance, protester Wietske Miedema tells Folia that she joined an action group through her lover. During a meeting of students with the university administration in the Maagdenhuis, she suddenly shouted: “The Maagdenhuis has opened up!” Five hundred of the thousand people present, thereupon started occupying the building.

Protesters also called for the democratization of the UvA during the Maagdenhuis occupation in February 2015. Philosophy students set up the action group Humanities Rally during a lecture earlier that year. Such groups of students, formed in student houses, lectures or when going out, also made up the core of the protests at the time, each time providing opportunities for other activist students to join.

Growth of occupations

According to historian Knegtmans, television played a major role during the 1969 Maagdenhuis occupation and other (social) media during the 2015 and 2024 occupations. “Those media also allowed the movement to blow over from the United States to the Netherlands last year.” Student Van Eck thinks otherwise. “Students continue to meet each other primarily at lectures or get-togethers. That is precisely where you can talk about social situations together.”

The pro-Palestine movements could grow faster after their initial beginnings, however, because in recent years there has been more cooperation between various action groups again, says lecturer-researcher Verlaan. Groups not composed exclusively of students such as Extinction Rebellion, MokumKraakt and Scientist Rebellion were formed in recent years in response to crises in national politics. “Groups fighting the climate crisis or housing shortage are now in solidarity with other action groups fighting other social injustices, such as Palestine.”

Also in 2015, initiator Humanities Rally of philosophy students received support from other groups such as the activist student party Ons Kritisch Alternatief. Once an initial occupation by one group succeeds, other activist groups, from Amsterdam and beyond, tend to join in. “I never thought: We are going to occupy the Maagdenhuis!,” founder of the smaller student movement Ons Kritisch Alternatief Jaap Oosterwijk said to Folia in 2020.

Why demonstrating?

That collaboration between general leftist groups and students takes place more easily in a left-leaning city such as Amsterdam, Verlaan thinks. History student Van Eck adds: “It is precisely here that students come to see the city and the university as tolerant and progressive.

Professor of pedagogy Femke Kaulingfreks, who researches youth participation, adds: “As a young person, you automatically start detaching yourself from your parents. You start questioning and contrasting what the previous generation did. That is necessary for activism.”

“There is no time and money nowadays for young people to fail, experiment and discover and thus to connect with other people in society,” Kaulingfreks continues. It is precisely this distance from society that makes students want to oppose it, describes colleague Verlaan. “With increasingly right-wing governments, left-wing, Amsterdam students think: these decisions oppose me and affect me personally. And so that group is now taking to the streets more often.”

University response

Another common denominator in the occupations over the years has been the use of police violence and the discussion about it. In 2015, for instance, police violence during the smaller Bungehuis occupation already led to the Maagdenhuis occupation of hundreds of students. “Don”t fight, don”t fight,” the 1969 occupiers still scanned as they were pulled out of the Maagdenhuis. The students are peaceful and the university is not, protesters within all occupations argue. Lecturer Verlaan: “Police intervention creates a spiral of violence from which there is no way out.”

Kaulingfreks, too, would have preferred the administration to go behind the barricades and talk to the protesters that Monday. “At the core, protesters want to talk to the university about values to be embraced. Caring, solidarity, compassion. In that, everyone can agree. Right?”