How table salt is one of the biggest threats to ancient art

Salt poses a major threat to the preservation of historical monuments, pottery and statues. The UvA, in collaboration with the Rijksmuseum, is researching this phenomenon to try and stop it. “Special frescoes or Delft blue tiles are almost irreparably affected by this.”

It may sound strange, but table salt - or sodium chloride - along with other salts, is one of the biggest threats to works of art such as murals, pottery or historical monuments made of natural stone. The crystallisation of water-soluble salts in porous materials leads to serious damage to, for example, the tombs in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, the temple of Petra in Jordan, or houses in Venice. But think also of statues, frescoes, and glazed tiles, such as the Delft blue ones.

Those salts are often already present in the rock or pottery, but can also come from the environment. “In the case of Venetian buildings, think of the salty seawater creeping up through the walls,” says Noushine Shahidzadeh, professor of Crystallization in Porous Media at the UvA. “In addition, there are salts in groundwater and air. Animal faeces but also road salt in winter contribute to this in large cities.”

Salt crystallisation in detail

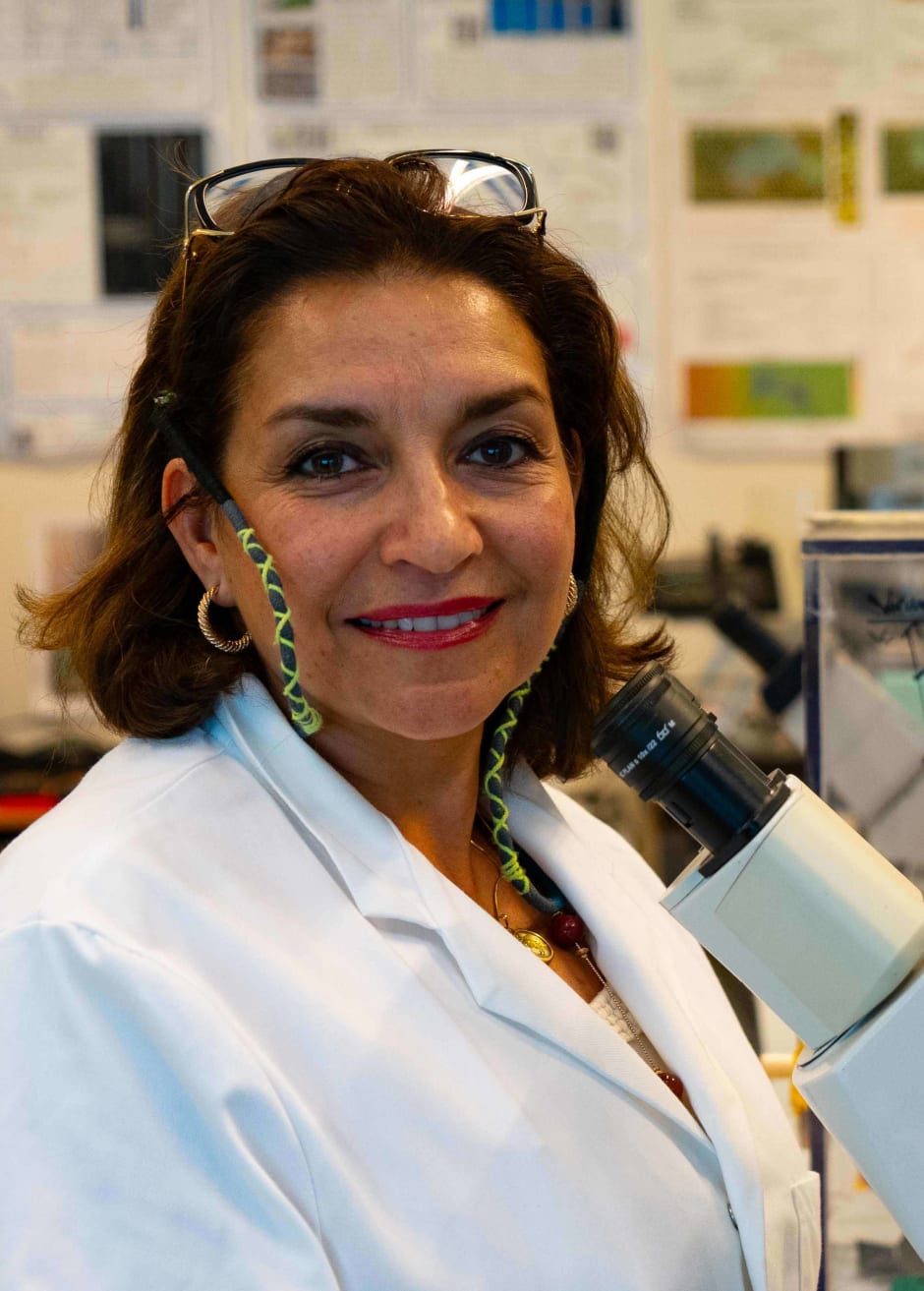

Shahidzadeh has been researching salt damage in cultural heritage for years. In her laboratory at Science Park, among the scales and microscopes, pieces of sandstone, a small statue from her own garden and some fragments of old Amsterdam churches are set up. “Here we are trying to gain insight into how salts behave in the pores of rocks and pottery,” Shahidzadeh continues as she points out the damage. “This is because temperature fluctuations and the changing moisture content in the air allow salts in the porous materials to dissolve, be transported and re-crystallise elsewhere. In the process, we examine the creep rate and crystallisation.”

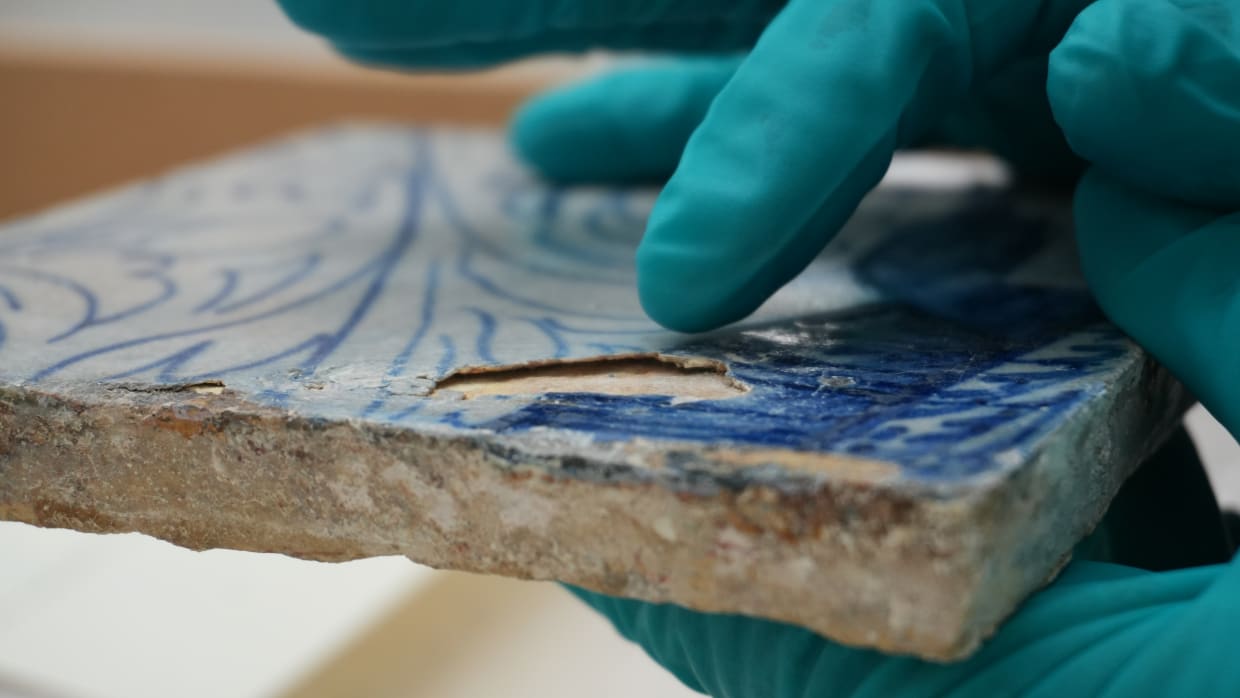

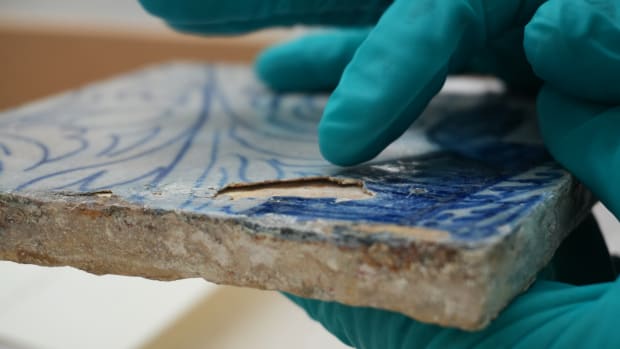

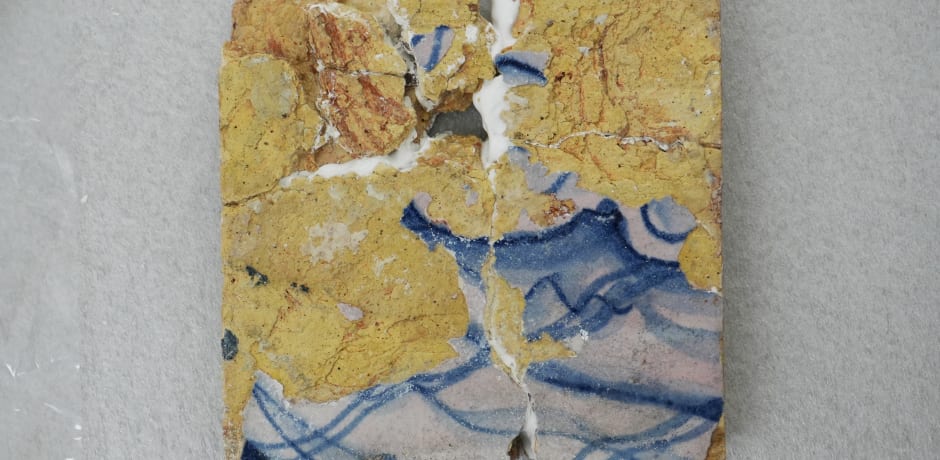

Salt crystallisation is ultimately the big culprit. Once salt crystallises, the salts in the pores of pottery and stone layers generate a pressure which causes the material to break or crumble. Isabelle Garachon, head of the ceramic, glass and stone restoration studio at the Rijksmuseum, sees the damage in busts, terracotta (decorative pottery), but especially glazed tiles, such as the tile tableau with a blue-painted portrait of Prince Maurits from 1615. “Tiles are extra fragile because the top layer is made of vitreous glaze and the bottom layer of fired clay. Once salts become active in the layer between them, damage occurs quite quickly. The same applies to Italian frescoes.”

Shahidzadeh and Garachon are collaborating under the European project Crystinart (Crystallization at interfaces of Artworks) to better understand the action of salts in porous layered materials and develop better conservation strategies. “We apply the insights Noushine is gaining about salt crystallisation in the studio by looking for new conservation techniques or tools that we can use in the restoration of cultural heritage,” says Garachon.

One of the most difficult tasks facing the researchers is the diversity of salts that may be present in the porous material. “For each of these salts, we want to know how fast they can move in the dissolved state, and in what way they crystallise,” Shahidzadeh explains. “Sodium chloride, for example, reacts differently to a changing climate than, say, sodium sulphate, which glazed tiles suffer from a lot. So to treat an object, we first need to know what kind of salts we are dealing with and what properties they have.”

(text continues below image)

Solutions

Once salt damage occur, there are few solutions. “For objects in museums, you can take climatic measures such as maintaining the temperature and relative humidity in a way that keeps the salt in place and prevents crystallisation,” says Shahidzadeh. “That is easy to do in museums, but for outdoor works of art like the Roman Forum in Rome, it is impossible. With rising temperatures and flooding from intense rainfall caused by climate change, salt crystallisation and hence damage will only increase. Floods will dissolve the salts which will then be transported and crystallise elsewhere.”

Nevertheless, research on salt crystallisation offers increasing insights that help preserve cultural heritage. “Desalination using compresses is another strategy to remove the salt from rocks or pottery. This works similar to applying a clay mask to your face for cleansing,” Shahidzadeh continues. “In addition, to prevent sculptures, for example, from crumbling due to salt crystallisation, gels are being developed to strengthen the material. Such a gel has to be very material-specific, which requires a lot of research. Clay or carbonate rocks are chemically very different from sandstone, for example. The idea is that the gel covers the grains on a microscopic scale but does not block the pores of pottery or sculptures. Those pores are important to prevent other forms of weathering damage.”

A lot has also changed in the studio over the past decades. “Before the 1990s, salt damage was counteracted by desalinating artefacts. Porous materials were then put into containers of water to dissolve the salt,” says Garachon. “But it’s quite a drastic treatment. After all, you force a kind of migration of salts out of the material. Moreover, you run the risk of the material still crumbling due to moisture.”

It is also looking at using other types of cleaning agents during restoration other than water and chlorine. “For a long time, bleach was used to clean artefacts properly, but through research we now know that the chlorine molecules in bleach can bind with sodium, which can actually create salt molecules in the material,” says Garachon. “So that knowledge of real-world problems and basic science ensures that we can preserve cultural heritage ever better.”